L'aereo - Typhoon - Myouth - Ricordi degli anni '70

Menu principale:

L'aereo - Typhoon

Modellismo > Aerei > Hawker Typhoon

Hawker Typhoon Mk.1B

Pilota dell'aereo riprodotto: Charles Llewellyn Green

Nazionalità: Rodesia

Divisione: 121° Squadrone Royal Air Force

Gruppo di Combatimento: ????

Squadrone di Combattimento: ??

Anno: 1944

Il pilota, Charles Llewellyn Green

L'Hawker Typhoon

L'Hawker Thypoon fu un aereo monomotore, monoplano ad ala bassa progettato dall'azienda britannica Hawker Aircraft sul finire degli anni trenta come aereo da caccia con il quale sostituire il precedente Hurricane, di recente entrato in servizio.

Alcuni problemi nello sviluppo ritardarono la sua messa in opera ma, una volta risolti, diventò il principale cacciabombardiere della Royal Air Force durante il secondo conflitto mondiale. Rimase in servizio fino al 1945, quando fu rimpiazzato dall'Hawker Tempest.

Storia del progetto

1)Sviluppo

Il progetto del Typhoon nacque nella primavera del 1937 quando i progettisti dell'Hawker Aircraft di Kingston, guidati dall'ingegnere Sydney Camm, iniziarono a lavorare al successore del caccia Hurricane appena entrato in servizio nella Royal Air Force: su iniziativa dell'azienda, fu portato a termine il progetto (denominato "Tipo N") di un velivolo con motore Napier Sabre, un 24 cilindri ad H allora in fase di sviluppo; il progetto fu sottoposto all'Air Ministry a luglio: la risposta, arrivata il mese dopo, invitava la Hawker ad attendere una specifica richiesta in materia, di imminente emanazione.

Sydney Camm ed il suo staff si concentrarono quindi su un secondo analogo progetto ("Tipo R"), che si distingueva prevalentemente per l'impiego del motore a 24 cilindri a X Rolls-Royce Vulture; questa seconda ipotesi era cautelativa, nell'eventualità che il progetto del motore Sabre non fosse giunto a compimento.

Nel gennaio 1938 l'Air Ministry rese pubblica una prima stesura della specifica "F.18/37" che fissava i requisiti relativi ad un nuovo velivolo da caccia, che avrebbe dovuto impiegare un motore da circa 2 000 hp (valori di potenza previsti in sede progettuale sia per il Sabre che per il Vulture) ed armamento costituito da dodici mitragliatrici Browning calibro .303 in; secondo almeno una fonte, fu presa in considerazione la possibilità di impiegare quattro cannoni calibro 20 mm (anche in questo caso l'Air Ministry faceva affidamento su un progetto in via di definizione, che poi portò al cannone automatico Hispano-Suiza HS.404).

La stesura definitiva della specifica ministeriale fu emessa nei primi giorni di aprile del 1938 e l'ultimo giorno di quello stesso mese la Hawker presentò le proprie proposte, all'epoca ancora tra loro alternative, dichiarandosi disponibile a realizzare due prototipi per ogni tipo; i progetti furono valutati con favore e quattro mesi dopo l'Hawker ricevette il benestare per la realizzazione delle due coppie di aerei.

I due velivoli erano tra loro molto somiglianti, distinguendosi prevalentemente per la disposizione del radiatore del liquido di raffreddamento: nel "Tipo R", cui venne assegnato il nome "Tornado", era disposto nel ventre della fusoliera (soluzione che tradiva la parentela del nuovo aereo con l'Hurricane) mentre nel "Tipo N", battezzato "Typhoon" era sistemato all'estremità anteriore, sotto il motore, a formare il caratteristico mento. Peculiarità condivisa dai due modelli era l'accesso alla cabina di pilotaggio, che avveniva tramite sportelli simili a quelli delle auto (soluzione analoga a quella del caccia statunitense P-39).

Nell'autunno del 1939 la costruzione del "Tipo R" aveva raggiunto uno stadio più avanzato, poiché le consegne del motore Sabre erano in ritardo: l'esemplare con numero di serie P5219 andò in volo per la prima volta a Langley (nel Buckinghamshire) il 6 ottobre 1939 ai comandi del collaudatore della Hawker, Philip Gadesden Lucas.

Prima della fine del 1939, poche settimane dopo il primo volo del prototipo, alla luce degli ottimi risultati ottenuti nelle prove l'Hawker Aircraft ricevette un ordine per 1 000 esemplari dei due nuovi velivoli. Di questi 500 sarebbero stati Tornado Mk.I e 250 Typhoon Mk.I, mentre i rimanenti 250 esemplari sarebbero stati ordinati sulla base di un confronto tra i due velivoli, volto a determinare quale dei due motori era il migliore; all'epoca, il prototipo del Typhoon era ancora a terra (avrebbe volato solo il 24 febbraio del 1940), ma con lo scoppio della guerra il Regno Unito aveva assoluta necessità di aerei da combattimento ed i due progetti non erano più alternativi fra di loro.

La primavera del 1940, con gli inglesi in difficoltà nel corso della campagna di Francia, portò alla revoca di qualsiasi priorità del Tornado per consentire alla Hawker di concentrarsi sugli Hurricane. Il prototipo del Typhoon (matricola P5212) aveva evidenziato carente stabilità direzionale per cui fu riportato a Kingston per modifiche all'impennaggio; durante questa sua permanenza in officina il Typhoon fu seriamente danneggiato da un bombardamento tedesco.

Poco dopo la ripresa dei voli di prova il Typhoon ebbe un cedimento strutturale nella zona immediatamente posteriore all'abitacoloe solo grazie all'abilità del collaudatore (ancora Philip Lucas che, per la maestria ed il coraggio dimostrati nell'occasione, fu insignito della George Meda) l'aereo fu ricondotto al suolo; il cedimento fu attribuito alle modifiche apportate ai piani di coda e si rimediò al volo.

Oltre alle frequenti interruzioni dovute alla necessità di revisionare con cadenza ravvicinata il fragile motore Sabre, il programma di prove, durato circa sei mesi, fu completato quasi interamente dal primo prototipo; il secondo velivolo (matricola P5216) volò per la prima volta il 3 maggio 1941, incorporando anche le prime modifiche ai portelli del carrello d'atterraggio. Durante queste prove alla base RAF Boscombe Down, i piloti collaudatori espressero perplessità sulle potenzialità del Typhoon come aereo da caccia ed i loro dubbi raggiunsero l'Air Ministry che s'interrogò sull'opportunità della produzione in serie dell'aereo.

Nel frattempo sul secondo prototipo erano stati installati i quattro cannoni calibro 20 mm al posto delle dodici mitragliatrici; la comparsa di problemi al sistema di alimentazione dei proiettili contribuì a incrementare i timori sulla sorte del progetto ai vertici della Hawker. L'Air Ministry nutriva poi il timore che il nemico potesse avere la meglio nei cieli grazie alle prestazioni del Focke-Wulf Fw 190 appena entrato in servizio; decise perciò di accelerare lo sviluppo del Typhoon acconsentendo definitivamente alla sua produzione in serie; il primo esemplare uscì dalle officine della Gloster Aircraft Company (società controllata dalla Hawker) il 27 maggio del 1941.

La produzione si articolò su due varianti, differenti per armamento: gli esemplari con mitragliatrici furono denominati Mk.IA e quelli con cannoni calibro 20 mm Mk.IB; per quanto riguarda il motore, nel corso della produzione del primo lotto di 250 aerei l'inaffidabile versione "I" del Sabre fu sostituita dalla recente variante "II", con un guadagno di circa 80 hp di potenza.

Le prime esperienze operative furono funestate da una serie di incidenti che per qualche tempo, anche per l'assenza di testimoni oculari, rimasero inspiegabili; in seguito, nel corso di un combattimento, si scoprì che la causa era strutturale: al termine di una manovra di picchiata compiuta per attaccare velivoli nemici si poteva staccare il tronco di coda della fusoliera . I tecnici dell'Hawker ricordarono il primo incidente al prototipo e si resero conto che a causa dei ristretti tempi di sviluppo richiesti, la fragilità della struttura era un dato di fatto. La soluzione fu relativamente semplice e si ricorse ad una serie di piastre di rinforzo rivettate nella parte della struttura soggetta a cedimenti.

Nel corso degli anni successivi il Typhoon fu soggetto a progressivi affinamenti: furono risolti i problemi all'alimentazione dei cannoni, sostituiti gli sportelli d'accesso con un cupolino a goccia scorrevole e installati motori "Sabre II" nelle varianti B e C azionanti eliche quadripala. L'unico problema non completamente risolto era rimasto il ritorno di fiamma al motore nella fase di avviamento, che non di rado si concludeva con la distruzione dell'aereo (tra il 1944 ed il 1945 ventotto aerei andarono persi così).

2)Tecnica

Cellula

L'Hawker Typhoon era un monoplano ad ala bassa dalla struttura metallica; la parte anteriore della fusoliera era costituita da un traliccio di tubi d'acciaio, che all'estremità anteriore si collegava, per mezzo di bulloni erivetti, al castello motore realizzato in modo analogo. Anche la radice delle ali era in traliccio di tubi, in questo caso realizzati in lega leggera. La parte posteriore della fusoliera aveva invece struttura a semiguscio con rivestimento lavorante, tecnica impiegata anche per la parte esterna delle ali-

La cabina di pilotaggio, disposta in posizione leggermente avanzata rispetto al centro del velivolo, era accessibile mediante aperture automobilistiche su entrambi i lati ed era sovrastata da una vetratura sostenuta da intelaiatura metallica che, nella versione Mk.IA, terminava immediatamente alle spalle del pilota per lasciare spazio ad una carenatura metallica che la raccordava alla fusoliera; nella versione Mk.IB la vetratura venne estesa anche alla carenatura di raccordo. Nel corso della produzione del terzo lotto di velivoli fu introdotto il tettuccio "a bolla", scorrevole verso la coda; il nuovo tettuccio fu progressivamente installato anche su gran parte gli esemplari di precedente produzione.

Le ali avevano il bordo d'entrata rettilineo e quello d'uscita rastremato verso le estremità e presentavano andamento ad ala di gabbiano invertito: la sezione interna presentava un leggero diedro negativo e la parte più esterna formava un leggero angolo positivo.

L'impennaggio era di tipo classico, ma l'equilibratore, disposto alla base della deriva, terminava anteriormente al timone e pertanto non richiedeva le caratteristiche smussature diagonali per permetterne il movimento; la forma dei piani verticali era semi-ovale, troncata verticalmente nella parte posteriore.

Il carrello d'atterraggio di tipo classico era interamente retrattile; le gambe anteriori, monoruota, erano imperniate nelle semiali circa alla metà della loro lunghezza e si ritraevano con movimento laterale verso l'interno dell'ala con meccanismo comandato idraulicamente

Motore

Il Typhoon nacque e si sviluppò unicamente intorno al Napier Sabre a 24 cilindri ad H raffreddati a liquido, realizzato dalla Napier Aero Engines che impiegava il sistema delle valvole a fodero.

Il Sabre sviluppava (almeno nominalmente) potenze elevate ma fu afflitto a lungo da scarsa affidabilità: il primo dei prototipi fu costretto a frequenti sospensioni delle prove, poiché il motore doveva essere revisionato ogni dieci ore di utilizzo, intervallo salito a 25 ore al momento dell'entrata in servizio nei reparti della RAF.

Il Sabre utilizzava il sistema di accensione "Coffman" che poteva causare ritorni di fiamma a volte disastrosi.

La Napier riuscì a risolvere i problemi e le versioni "IIB" e "IIC" raggiungevano e superavano i 2.200 hp di potenza (pari a 1 640 kW); accoppiate a queste versioni del motore comparvero sul Typhoon eliche quadripala della de Havilland o dalla Rotol.

3) Armamento

Secondo quanto stabilito dalla specifica originaria, il Typhoon fu progettato con dodici mitragliatrici Browning calibro .303 in, ma già il secondo prototipo fu dotato di quattro cannoni Hispano-Suiza HS.404 calibro 20 mm. Tra gli esemplari di serie, quelli appartenenti alla variante denominata Mk.IA (circa cento) furono gli unici equipaggiati con mitragliatrici. Gli esemplari dotati dei cannoni erano identificabili dalle canna dei cannoni, considerevolmente sporgenti dal bordo d'entrata dell'ala.

Dai primi mesi del 1942 il Typhoon fu sottoposto ad un intenso ciclo di prove destinate a valutare l'impiego di carichi esterni: dapprima fu approvato l'uso di serbatoi supplementari sganciabili poi fu la volta di bombe (fino a due da 500 lb ciascuna, poco meno di 227 kg l'una), bombe fumogene, mine e infine proiettili razzo da 3 in, alloggiati su apposite rotaie agganciate nell'intradosso alare, esternamente alle gambe del carrello d'atterraggio (quattro per ogni semiala).

In seguito al buon esito in battaglia dei cannoni, la Hawker produsse un certo numero di ali equipaggiate con sei cannoni HS.404, mai utilizzate..

Impiego operativo

La decisione di introdurre il Typhoon nella RAF fu presa nell'estate del 1941 e fu condizionata dalle notizie sul prossimo schieramento del Focke-Wulf Fw 190 della Luftwaffe; in effetti la comparsa dei due velivoli sul fronte occidentale fu contemporanea: i nuovi caccia tedeschi furono schierati a Moorseele, in Belgio, nelle file del II Gruppo dello Jagdgeschwader 26 (26º Stormo Caccia), i Typhoon furono assegnati al No. 56 Squadron della RAF, alla base aerea di Duxford, presso Cambridge.

Sulla scelta del reparto incise il fatto che la pista dell'aerodromo di Duxford fosse in erba, che avrebbe contribuito a rallentare gli aerei nella fase di atterraggio, elemento utile nel caso del Typhoon afflitto inizialmente da un impianto frenante non particolarmente efficace.

Le prime operazioni con il Typhoon (ribattezzato affettuosamente Tiffy o Tiffie dal personale della RAF) portarono alla luce i problemi rilevati durante i collaudi: difficoltà in accensione e principi d'incendio al motore, infiltrazione nell'abitacolo di monossido di carbonio proveniente dai gas di scarico (causata dalla cattiva tenuta delle guarnizioni delle paratie), scarsa visibilità al posteriore oltre ai già citati cedimenti strutturali. Nei registri di volo restano tracce di incidenti considerevoli occorsi a 135 dei primi 142 Typhoon per cause non dipendenti dal nemico.

Progressivamente però, grazie all'esperienza maturata ed alla risoluzione dei problemi, il Typhoon cominciò a farsi apprezzare: la sua robustezza fu tra i fattori che contribuirono alla perdita di due soli piloti tra l'autunno del 1941 e l'agosto del 1942. I piloti si resero conto che era rischioso affrontare gli aerei nemici con duelli acrobatici alle alte quote mentre l'aereo si rivelò particolarmente adatto a contrastare gli attacchi a bassa quota dai cacciabombardieri tedeschi, anche se il primo abbattimento di un FW 190 ad opera di un Typhoon arrivò solo il 17 ottobre 1942.

Tra i vari pericoli per i piloti dei primi Typhoon vi fu la pericolosa somiglianza, in caso di particolari angoli di visuale, con il FW 190: furono almeno quattro gli abbattimenti registrati ad opera di caccia Spitfire amici, prima che (alla fine del 1942) fossero applicate strisce bianche e nere alle superfici inferiori delle ali.

Condizionati dalle ridotte prestazioni alle quote più elevate e dal potenziale pericolo di perdere la coda al termine di una picchiata, i Typhoon furono presto destinati alle operazioni a quote relativamente basse, in particolare al contrasto dei cacciabombardieri tedeschi nelle loro scorrerie definite "hit-and-run": si trattava di missioni compiute da coppie o singoli velivoli (in genere i nuovi FW 190) a quote estremamente basse, per cui il pattugliamento dei Typhoon avveniva a 200 ft (all'incirca 60 m). La frequente inoperosità in queste missioni condusse i comandanti delle squadriglie a chiedere di compiere azioni offensive e portò a sperimentare la possibilità di dotare gli aerei di carichi di caduta.

Con il passare dei mesi l'impiego del Typhoon divenne sempre più diffuso e lo stormo basato a Duxford (Squadron 56, 266 e 609) nel mese di agosto fu compreso nelle forze schierate in occasione del raid su Dieppe. Prima della fine dell'anno gli Squadron dotati del nuovo caccia furono tredici, cui se ne aggiunsero altri sei entro l'aprile del 1943.

Dall'autunno 1942 fu autorizzato l'impiego di bombe subalari ed il Typhoon cominciò ad affermarsi prevalentemente come cacciabombardiere; poiché le sue prestazioni erano marginalmente condizionate dalla presenza delle bombe, ben presto iniziarono le prove per raddoppiarle, completate ai primi del 1944. I Bombphoons, come in alcuni casi furono soprannominati, operavano sia di giorno che di notte puntando con sempre maggiore frequenza ai convogli ferroviari tedeschi in territorio francese; per altro le missioni come caccia non cessarono completamente: tra queste le operazioni di scorta ai Whirlwind ed ai Beaufighter nelle missioni di attacco alle navi nel canale della Manica.

Il 1943 registrò un ulteriore incremento nel numero dei reparti equipaggiati con i Typhoon, mentre la macchina veniva affinata e resa più efficace: l'impiego di serbatoi aggiuntivi (subalari) consentì di raggiungere le frontiere tedesche e attaccare con sempre maggiore costanza le linee di rifornimento nemiche. Crebbe anche il numero degli aerei abbattuti: nel corso dell'anno furono 380 gli aerei perduti (indipendentemente dalla causa). Tuttavia, grazie alla robustezza della struttura molti aerei riuscirono a rientrare alle basi, e nello stesso periodo i Typhoon riuscirono ad abbattere in combattimento 103 aerei, tra i quali 52 FW 190.

La modifica di maggior riguardo portò all'adozione di rotaie destinate al lancio di proiettili-razzo sotto le ali: prodotti su larga scala e già installati sui Mosquito, Beaufighter, Hurricane e Swordfish, il loro impiego ebbe inizio nell'autunno del 1943 facendo del Typhoon una delle armi più potenti a disposizione della RAF. Un Typhoon montava in genere otto rotaie subalari ma nel tempo furono realizzate varianti del sistema di aggancio che consentivano di trasportare fino ad otto razzi per ala.

Nel novembre del 1943 la Royal Air Force creò la 2nd Tactical Air Force, cui sarebbe stato affidato il supporto aereo dell'imminente invasione del continente europeo (l'operazione Overlord): la riorganizzazione dei reparti di volo avvenuta nei mesi successivi portò all'interno di questa struttura i reparti equipaggiati con Typhoon, tranne due che rimasero alle dipendenze del Fighter Command.

Nella primavera del 1944 i Typhoon furono anche impiegati per sperimentare un sistema di rilevazione dei segnali emessi dai radar di identificazione tedeschi; il sistema, noto con il nome di "Abdullah", richiedeva la preventiva conoscenza della frequenza di lavoro del radar e non si rivelò più efficiente delle informazioni sui siti ottenute con operazioni di intelligence o della ricognizione fotografica e pertanto fu abbandonato.

Il giorno dello sbarco, il 6 giugno, i Typhoon protessero i settori destinati alle forze britanniche e canadesi; in particolare il loro obiettivo principale erano i mezzi corazzati tedeschi, generalmente vittoriosi sugli attaccanti. Per consentire un rapido intervento dell'aviazione in appoggio alle truppe di terra, già dal secondo giorno di operazioni fu data la priorità alla costruzione di piste di volo ed i Typhoon furono tra i primi aerei a posarvisi; la reazione tedesca costrinse le forze aeree ad un repentino rischieramento sulle basi inglesi, il che consentì l'installazione di nuovi filtri dell'aria sui Typhoon, che soffrivano particolarmente la fine polvere che si sollevava dai campi della Normandia.

La costante presenza dei Typhoon e l'impiego di nuovi ed efficaci sistemi di coordinamento degli interventi (guidati direttamente da terra, tramite ufficiali operanti nei pressi delle avanguardie) garantirono la possibilità di attacchi "a richiesta", come nei combattimenti nella sacca di Falaise, conclusi il 21 agosto. Alla metà del mese successivoSquadrons equipaggiati con Typhoon furono trasferiti nelle basi in Belgio e prima della fine del mese fu la volta di quelle olandesi, dalle quali era possibile operare direttamente in territorio tedesco.

In dicembre, nel corso della offensiva delle Ardenne, la Luftwaffe pose in atto l'operazione Bodenplatte nel corso della quale due stormi operanti dalla base di Eindhoven causarono la perdita di diciannove Typhoon e altri quattordici danneggiati; in febbraio del 1945 i Typhoon erano di nuovo all'attacco nel corso dell'operazione Veritable e le loro operazioni si protrassero fino agli ultimi giorni di guerra: nel solo mese di aprile furono almeno trentotto i cacciabombardieri abbattuti ad opera della FlaK. I Typhoon ebbero modo di confrontarsi anche con gli aerei a getto tedeschi: le fonti riportano l'abbattimento di tre Messerschmitt Me 262 (due il 14 febbraio ed uno il 23 aprile). L'ultimo velivolo tedesco a cadere sotto i colpi del Typhoon fu un Blohm & Voss BV 138 che tentava di sfuggire ad un attacco alla propria base, il 3 maggio del 1945.

Il Typhoon non sopravvisse alla fine della guerra: solo alcuni esemplari furono impiegati per il traino di bersagli, ma la maggior parte fu radiata dai reparti di volo.

Fonte: Wikipedia

Hawker Typhoon

The Hawker Typhoon (Tiffy in RAF slang) is a British single-seat fighter-bomber, produced by Hawker Aircraft. It was intended to be a medium–high altitude interceptor, as a replacement for the Hawker Hurricane but several design problems were encountered and it never completely satisfied this requirement.

The Typhoon was originally designed to mount twelve .303 inch (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns and be powered by the latest 2,000 hp engines. Its service introduction in mid-1941 was plagued with problems and for several months the aircraft faced a doubtful future. When the Luftwaffe brought the formidable Focke-Wulf Fw 190 into service in 1941, the Typhoon was the only RAF fighter capable of catching it at low altitudes; as a result it secured a new role as a low-altitude interceptor.

The Typhoon became established in roles such as night-time intruder and long-range fighter. From late 1942 the Typhoon was equipped with bombs and from late 1943 RP-3 rockets were added to its armoury. With those weapons and its four 20mm Hispano autocannons, the Typhoon became one of the Second World War's most successful ground-attack aircraft.

Development and production

1)Origins

Even before Hurricane production began in March 1937, Sydney Camm had embarked on designing its successor. Two preliminary designs were similar and were larger than the Hurricane. These later became known as the "N" and "R" (from the initial of the engine manufacturers), because they were designed for the newly developed Napier Sabreand Rolls-Royce Vulture engines respectively. Both engines used 24 cylinders and were designed for over 2,000 hp (1,500 kW); the difference between the two was primarily in the arrangement of the cylinders – an H-block in the Sabre and an X-block in the Vulture. Hawker submitted these preliminary designs in July 1937 but were advised to wait until a formal specification for a new fighter was issued.

In March 1938, Hawker received from the Air Ministry, Specification F.18/37 for a fighter which would be able to achieve at least 400 mph (640 km/h) at 15,000 feet (4,600 m) and specified a British engine with a two-speed supercharger. The armament fitted was to be twelve .303 inch Browning machine guns with 500 rounds per gun, with a provision for alternative combinations of weaponry. Camm and his design team started formal development of the designs and construction of prototypes.

The basic design of the Typhoon was a combination of traditional Hawker construction (such as used in the earlier Hawker Hurricane) and more modern construction techniques; the front fuselage structure, from the engine mountings to the rear of the cockpit, was made up of bolted and welded duralumin or steel tubes covered with skin panels, while the rear fuselage was a flush-riveted, semi-monocoque structure. The forward fuselage and cockpit skinning was made up of large, removable duralumin panels, allowing easy external access to the engine and engine accessories and most of the important hydraulic and electrical equipment.

The wing had a span of 41 feet 7 inches (12.67 m), with a wing area of 279 sq ft (29.6 sq m). It was designed with a small amount of inverted gull wing bend; the inner sections had a 1° anhedral, while the outer sections, attached just outboard of the undercarriage legs, had a dihedral of 5½°. The airfoil was a NACA 22 wing section, with a thickness-to-chord ratio of 19.5% at the root tapering to 12% at the tip.

The wing possessed great structural strength, provided plenty of room for fuel tanks and a heavy armament, while allowing the aircraft to be a steady gun platform. Each of the inner wings incorporated two fuel tanks; the "main" tanks, housed in a bay outboard and to the rear of the main undercarriage bays, had a capacity of 40 gallons; while the "nose" tanks, built into the wing leading edges, forward of the main spar, had a capacity of 37 gallons each. Also incorporated into the inner wings were inward-retracting landing gear with a wide track of 13 ft 6¾ in.

By contemporary standards, the new design's wing was very "thick", similar to the Hurricane before it. Although the Typhoon was expected to achieve over 400 mph (640 km/h) in level flight at 20,000 ft, the thick wings created a large drag rise and prevented higher speeds than the 410 mph at 20,000 feet (6,100 m) achieved in tests. The climb rate and performance above that level was also considered disappointing.When the Typhoon was dived at speeds of over 500 mph (800 km/h), the drag rise caused buffeting and trim changes. These compressibility problems led to Camm designing the Typhoon II, later known as theTempest, which used much thinner wings with a laminar flow airfoil..

The first flight of the first Typhoon prototype, P5212, made by Hawker's Chief test Pilot Philip Lucas from Langley, was delayed until 24 February 1940 because of the problems with the development of the Sabre engine. Although unarmed for its first flights, P5212 later carried 12 .303 in (7.7 mm) Brownings, set in groups of six in each outer wing panel; this was the armament fitted to the first 110 Typhoons, known as the Typhoon IA. P5212 also had a small tail-fin, triple exhaust stubs and no wheel doors fitted to the centre-section. On 9 May 1940 the prototype had a mid-air structural failure, at the join between the forward fuselage and rear fuselage, just behind the pilot's seat. Philip Lucas could see daylight through the split but instead of bailing out, landed the Typhoon and was later awarded the George Medal.

On 15 May, the Minister of Aircraft Production, Lord Beaverbrook, ordered that resources should be concentrated on the production of five main aircraft types (the Spitfire and Hurricane fighters and the Whitley, Wellington and Blenheim bombers). As a result, development of the Typhoon was slowed, production plans were postponed and test flying continued at a reduced rate.

As a result of the delays the second prototype, P5216, first flew on 3 May 1941: P5216 carried an armament of four belt-fed 20 mm (0.79 in) Hispano Mk II cannon, with 140 rounds per gun and was the prototype of the Typhoon IB series. In the interim between construction of the first and second prototypes, the Air Ministry had given Hawker an instruction to proceed with the construction of 1,000 of the new fighters. It was felt that the Vulture engine was more promising, so the order covered 500 Tornadoes and 250 Typhoons, with the balance to be decided once the two had been compared. It was also decided that because Hawker was concentrating on Hurricane production, the Tornado would be built by Avro and Gloster would build the Typhoons at Hucclecote. Avro and Gloster were aircraft companies within the Hawker Siddeley group. As a result of good progress by Gloster, the first production Typhoon R7576 was first flown on 27 May 1941 by Michael Daunt, just over three weeks after the second prototype.

Operational service

Low-level interceptor

In 1941, the Spitfire Vs, which equipped the bulk of Fighter Command squadrons, were outclassed by the new Focke-Wulf Fw 190 and suffered many losses. The Typhoon was rushed into service with Nos. 56 and 609 Squadrons in late 1941, to counter the Fw 190. This decision proved to be a disaster and several Typhoons were lost due to unknown causes and the Air Ministry began to consider halting production of the type.

In August 1942, Hawker's second test pilot, Ken Seth-Smith, while deputising for Chief Test Pilot Philip Lucas, carried out a straight and level speed test from Hawker's test centre at Langley, and the aircraft broke up over Thorpe, killing the pilot. Sydney Camm and the design team immediately ruled out pilot error, which had been suspected in earlier crashes. Investigation revealed that the elevator mass-balance had torn away from the fuselage structure. Intense flutter developed, the structure failed and the tail broke away. Modification 286 to the structure and the control runs partially solved the structural problem. (The 1940 Philip Lucas test flight incident had been due to an unrelated failing.) Mod 286, which involved fastening external fishplates, or reinforcing plates, around the tail of the aircraft, and eventually internal strengthening, was only a partial remedy, and there were still failures right up to the end of the Typhoon's service life. The Sabre engine was also a constant source of problems, notably in colder weather, when it was very difficult to start, and it suffered problems with wear of its sleeve valves, with consequently high oil consumption. The 24-cylinder engine also produced a very high-pitched engine note, which pilots found very fatiguing.

The Typhoon did not begin to mature as a reliable aircraft until the end of 1942, when its excellent qualities — seen from the start by S/L Roland Beamont of 609 Squadron — became apparent. Beamont had worked as a Hawker production test pilot while resting from operations, and had stayed with Seth-Smith, having his first flight in the aircraft at that time. During late 1942 and early 1943, the Typhoon squadrons were based on airfields near the south and south-east coasts of England and, alongside two Spitfire XII squadrons, countered the Luftwaffe's "tip and run" low-level nuisance raids, shooting down a score or more bomb-carrying Fw 190s. Typhoon squadrons kept at least one pair of aircraft on standing patrols over the south coast, with another pair kept at "readiness" (ready to take off within two minutes) throughout daylight hours. These sections of Typhoons flew at 500 feet (150 m) or lower, with enough height to spot and then intercept the incoming enemy fighter-bombers. The Typhoon finally proved itself in this role; for example, while flying patrols against these low-level raids, 486(NZ) Squadron claimed 20 fighter-bombers, plus three bombers shot down, between mid-October 1942 and mid-July 1943.

The first two Messerschmitt Me 210 fighter-bombers to be destroyed over the British Isles fell to the guns of Typhoons in August 1942. During a daylight raid by the Luftwaffe on London on 20 January 1943, four Bf 109G-4s and one Fw 190A-4 of JG 26 were destroyed by Typhoons. As soon as the aircraft entered service, it was apparent the profile of the Typhoon resembled a Fw 190 from some angles, which caused more than one friendly fire incident involving Allied anti-aircraft units and other fighters. This led to Typhoons first being marked up with all-white noses, and later with high visibility black and white stripes under the wings, a precursor of the markings applied to all Allied aircraft on D-Day.

Switch to ground attack

By 1943, the RAF needed a ground attack fighter more than a "pure" fighter and the Typhoon was suited to the role (and less-suited to the pure fighter role than competing aircraft such as the Spitfire Mk IX). The powerful engine allowed the aircraft to carry a load of up to two 1,000 pounds (450 kg) bombs, equal to the light bombers of only a few years earlier. The bomb-equipped aircraft were nicknamed "Bombphoons" and entered service with No. 181 Squadron, formed in September 1942.

From September 1943, Typhoons were also armed with four "60 lb" RP-3 rockets under each wing. In October 1943, No. 181 Squadron made the first Typhoon rocket attacks. Although the rocket projectiles were inaccurate and took considerable skill to aim and allow for ballistic drop after firing, "the sheer firepower of just one Typhoon was equivalent to a destroyer's broadside. By the end of 1943, eighteen rocket-equipped Typhoon squadrons formed the basis of the RAF Second Tactical Air Force(2nd TAF) ground attack arm in Europe. In theory, the rocket rails and bomb-racks were interchangeable; in practice, to simplify supply, some 2nd TAF Typhoon squadrons (such as 198 Squadron) used the rockets only, while other squadrons were armed exclusively with bombs (this also allowed individual units to more finely hone their skills with their assigned weapons).

By the Normandy landings in June 1944, 2 TAF had eighteen operational squadrons of Typhoon IBs, while RAF Fighter Command had a further nine. The aircraft proved itself to be the most effective RAF tactical strike aircraft, on interdiction raids against communications and transport targets deep in North Western Europe prior to the invasion and in direct support of the Allied ground forces after D-Day. A system of close liaison with the ground troops was set up by the RAF and army: RAF radio operators in vehicles equipped with VHF R/T travelled with the troops close to the front line and called up Typhoons operating in a "Cab Rank", which attacked the targets, marked for them by smoke shells fired by mortar or artillery, until they were destroyed.

Against some of the Wehrmacht's heavier tanks, the rockets needed to hit the thin-walled engine compartment or the tracks to have any chance of destroying or disabling the tank. Analysis of destroyed tanks after the Normandy battle showed a "hit-rate" for the air-fired rockets of only 4%. In Operation Goodwood (18 to 21 July), the 2nd Tactical Air Force claimed 257 tanks destroyed. A total of 222 were claimed by Typhoon pilots using rocket projectiles. Once the area was secured, the British "Operational Research Section 2" analysts could confirm only ten out of the 456 knocked out German AFVs found in the area were attributable to Typhoons using rocket projectiles.

At Mortain, in the Falaise pocket, a German counter-attack that started on 7 August threatened Patton's break-out from the beachhead; this counter-attack was repulsed by 2nd Tactical Air Force Typhoons and the 9th USAAF. During the course of the battle, pilots of the 2nd Tactical Air Force and 9th USAAF claimed to have destroyed a combined total of 252 tanks. Only 177 German tanks and assault guns participated in the battle and only 46 were lost – of which nine were verified as destroyed by Typhoons, four percent of the total claimed.

However, after-action studies at the time were based on random sampling of wrecks rather than exhaustive surveys, and the degree of overclaim attributed to Typhoon pilots as a result was statistically improbable in view of the far lower known level of overclaim by Allied pilots in air-to-air combat, where claims were if anything more likely to be mistaken. Allied and German witness accounts of Typhoon attacks on German armour indicate that RPs did kill tanks with fair probability. Horst Weber, an SS panzergrenadier serving with Kampfgruppe Knaust south of Arnhem in the later stages of Operation Market Garden, recalled that, during a battle with British 43rd Wessex Division on 23 September 1944, 'We had four Tiger tanks and three Panther tanks... We were convinced that we would gain another victory here, that we would smash the enemy forces. But then Typhoons dropped these rockets on our tanks and shot all seven to bits. And we cried... We would see two black dots in the sky and that always meant rockets. Then the rockets would hit the tanks which would burn. The soldiers would come out all burnt and screaming with pain.'

The effect on the morale of German troops caught up in a Typhoon RP and cannon attack was decisive, with many tanks and vehicles being abandoned, in spite of superficial damage, such that, at Mortain, a signal from the German Army's Chief of Staff stated that the attack had been brought to a standstill by 13:00 '...due to the employment of fighter-bombers by the enemy, and the absence of our own air-support.' The 20 mm cannon also destroyed a large number of (unarmoured) support vehicles, laden with fuel and ammunition for the armoured vehicles. On 10 July at Mortain, flying in support of the US 30th Infantry Division, Typhoons flew 294 sorties in the afternoon that day, firing 2,088 rockets and dropping 80 short tons (73 t) of bombs. They engaged the German formations while the US 9th Air Force prevented German fighters from intervening. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, said of the Typhoons; "The chief credit in smashing the enemy's spearhead, however, must go to the rocket-firing Typhoon aircraft of the Second Tactical Air Force... The result of the strafing was that the enemy attack was effectively brought to a halt, and a threat was turned into a great victory."

Another form of attack carried out by Typhoons was "Cloak and Dagger" operations, using intelligence sources to target German HQs. One of the most effective of these was carried out on 24 October 1944, when 146 Typhoon Wing attacked a building in Dordrecht, where senior members of the German 15th Army staff were meeting; 17 staff officers and 36 other officers were killed and the operations of the 15th Army were adversely affected for some time afterwards.

On 24 March 1945, over 400 Typhoons were sent on several sorties each, to suppress German anti-aircraft guns and Wehrmacht resistance to Operation Varsity, the Allied crossing of the Rhine that involved two full divisions of 16,600 troops and 1,770 gliders sent across the river. On 3 May 1945, the Cap Arcona, the Thielbek and theDeutschland, large passenger ships in peacetime now in military service, were sunk in four attacks by RAF Hawker Typhoon 1Bs of No. 83 Group RAF, 2nd Tactical Air Force: the first by 184 Squadron, second by 198 Squadron led by Wing Commander John Robert Baldwin, the third by 263 Squadron led by Squadron Leader Martin T. S. Rumbold and the fourth by 197 Squadron led by Squadron Leader K. J. Harding.

The top-scoring Typhoon ace was Group Captain J. R. Baldwin (609 Squadron and Commanding Officer 198 Squadron, 146 (Typhoon) Wing and 123 (Typhoon) Wing), who claimed 15 aircraft shot down from 1942 to 1944. Some 246 Axis aircraft were claimed by Typhoon pilots during the war.

3,317 Typhoons were built, almost all by Gloster. Hawker developed what was originally an improved Typhoon II, but the differences between it and the Mk I were so great that it was effectively a different aircraft, and was renamed the Hawker Tempest. Once the war in Europe was over Typhoons were quickly removed from front-line squadrons; by October 1945 the Typhoon was no longer in operational use, with many of the wartime Typhoon units such as 198 Squadron being either disbanded or renumbered.

Source: Wikipedia

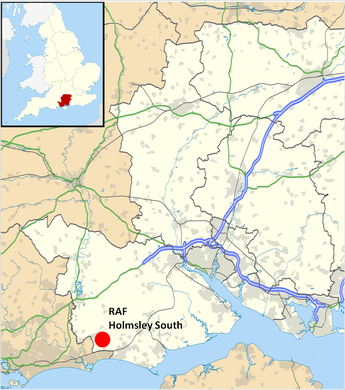

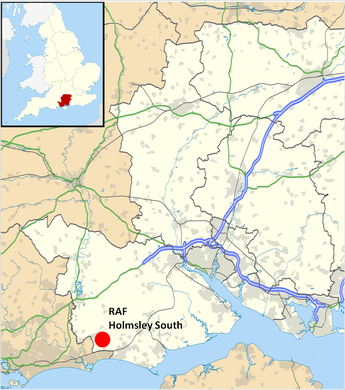

Aereoporto ove operava: RAF Holmsley South (UK)

Home Page | Modellismo | Topolini | Altri Disney | Linus | Asterix | Diabolik | Giornalini di guerra | Western | Riviste | Romanzi | Mappa generale del sito